From the bomb-shattered second floor window, Helga could see the gray sedan slowly creeping nearer, its slitted headlights piercing the rain and darkness as it weaved between the debris of fallen buildings. Trembling with fear, she turned to the old couple with her finger to her lips and motioned toward the icebox in the corner of the room. Glancing back toward the street, she saw the car stop in front of her building. The rear doors opened and two Gestapo agents stood staring at the front door of her building with their hands resting on their holstered weapons. One threw a cigarette onto the street. The other appeared to be checking the address. They nodded to each other, approached the door and rapped loudly. The sound was amplified as it came up the narrow hallway steps to the second floor.

From the bomb-shattered second floor window, Helga could see the gray sedan slowly creeping nearer, its slitted headlights piercing the rain and darkness as it weaved between the debris of fallen buildings. Trembling with fear, she turned to the old couple with her finger to her lips and motioned toward the icebox in the corner of the room. Glancing back toward the street, she saw the car stop in front of her building. The rear doors opened and two Gestapo agents stood staring at the front door of her building with their hands resting on their holstered weapons. One threw a cigarette onto the street. The other appeared to be checking the address. They nodded to each other, approached the door and rapped loudly. The sound was amplified as it came up the narrow hallway steps to the second floor.

Helga went to the icebox and gave it a firm pull, revealing a small door in the wall behind. The icebox had been empty since she moved in as food was extremely scarce and ice was unavailable. She motioned for them to hurry and the agents rapped louder and yelled something she did not hear well enough to understand.

“Offne die Tür! Zu dem Zeitpunkt. Snell!” Open the door. Now!

“Ich komme gleich runter,” she hollered. I’ll be right down.

After the old couple had passed through the door, she pushed the icebox back and ran down the stairs to open the door.

“Zur Seite gehen, fraulein,” step aside, the first one said, and he pushed her aside and climbed the steps two at a time.

“We will find them, fraulein,” the second said with a smirk. “We know they’re here.” Water dripped off the bill of the agent’s cap and his glasses were slightly fogged, but Helga knew those cold, steel eyes. She had seen them before.

Helga heard the floorboards creak as the agent upstairs slowly moved from room to room looking for the hidden Jewish couple. After a few moments, he walked down the steps and shrugged his shoulders to his partner.

“Nobody,” he said tersely and motioned toward the door as if to leave. As he passed Helga, he glanced at her and raised his eyebrows slightly, then the two agents disappeared into the night. Helga listened as their footsteps faded. She heard the car doors slam and the sedan slowly motored away.

Helga went back up the stairs and pulled the icebox away from the wall, telling the couple it was safe to come out. Then she sat on a kitchen chair, took several deep breaths, and tried to calm her nerves. She picked up a cup that had once held hot tea, but even using two hands, she could not hold it steady enough to drink.

Helga Stigler had lived in Bonn all her life. Both she and her husband Fritz were of Prussian descent and while they both believed in a strong Germany, they took exception to Nazi tactics and the oppression of the Jews. Fritz was a tank commander under General Hienz Guderian and was a leader in the blitz of Poland and France. However, when Guderian’s Panzers were transferred to spearhead the new Eastern Front, Fritz was demoted and in the fall of 1942, he was put in charge of a single tank crew, albeit a new Tiger II, which he affectionately referred to as his “konigstiger”. He had been sure his demotion was because of his soft attitude toward the oppression of the Jews and what was termed as the ‘final solution.’ Helga had not heard from Franz for several months and in her heart of hearts, she knew he was dead, or worse yet, imprisoned by the Russians.

When Franz was transferred, Helga realized she could not and would not stand by and ignore what was happening inside the Jewish ghettos of Bonn. She learned of a secret organization that helped sneak Jews out of Germany and back to unoccupied territory. Helga soon left her comfortable home and moved into a second floor, three-room flat inside the old walled section of Bonn where many Jews had been forced to live. She planned to use this apartment as a safe house where Jews could secretly stay. Helga contracted with an old Jewish carpenter who built a false wall that enclosed a very small space where several people could hide undetected. She knew that if she or any of Jews she assisted were ever caught, they would face certain torture and/or a firing squad.

Never planning to be taken alive, Helga obtained a bottle of zyankali pills which contained potassium cyanide in a glass ampule. She also gave an ampule to each of the Jews she hid. But none of this was enough for Helga. The allies were fast approaching and by the stream of men, materiel, and wounded heading back toward Berlin, she knew the war would be over very soon.

Near 4:00 in the afternoon, Helga went to her bedroom, changed into a simple skirt and blouse, powdered her nose and left the flat. It would take her exactly thirty minutes to arrive at her destination, and she knew the route well. Once there, she used her own key, unlocked the back door and went upstairs to the bedroom. She looked out the front window at the River Rhein flowing muddy brown, swollen by the heavy rains. Two major bridges lay in the water destroyed by allied bombing. She took off her clothes and, after neatly folding them, laid them on his dresser. She crawled into bed and waited.

After Helga had moved into her flat in the ghetto, she started to frequent several popular bars in the downtown area of Bonn, where soldiers and officers were often seen. She was forty-two years old, trim and still very attractive which meant she never paid for a drink, and her offers were numerous. But she was particular. She wanted something. Something that only a Gestapo officer could offer.

She finally met Hauptsturmfuhrer Metzler, a single, wealthy, Gestapo captain, who thought the war was just another adventure. He was several years younger than Helga, overweight, and always wet from perspiration. He liked to control anyone who would let him, and even though she hated his kind to her core, Helga made sure he thought he controlled her.

After several dates with the captain, Helga knew that he was perfect for what she had in mind. He wanted regular sex and she wanted somebody with the power to look the other way. Twice a week, she would come to his flat and in return, he would use his authority to allow her activities with the Jews to go unnoticed.

“Helga? Are you here?” the captain called as he entered the front door. He went straight to the bedroom to check. “Ah, yes. There you are, Honig,” he said relieved. He came to the bed and kissed her. He drew the covers back and saw she was naked. “Ah, perfect. Its been a long day,” he said sighing. “I’ve been thinking of you for some time.”

Helga watched him undress—and she began to build her wall. The wall that would enable her to isolate herself from him and the things she let him do. She had to separate her mind from her body. She would go through the motions, but her mind would not follow. Rather it would dwell on the goal line while her body pushed forward.

He was a terrible lover and that was a good thing. When he had taken off his clothes, he slowly pulled back the covers again and gazed at her. He was ready almost instantly. He lay on top of her. His forehead was beaded with sweat and his body smelled like dirty laundry. Helga closed her eyes. Her wall protected her and it was all over in a few minutes. He rolled over and she got up and started to dress.

“Stay for a drink?” He asked.

“No. I must go, but could I make you one?”

“Sure. Will I see you Thursday?” He asked. Then, he added, “I am being transferred back to Berlin. Soon, you will be free of us. Won’t that make you happy?”

She stopped in her tracks. “Berlin? Who will take your place?”

“What! You’re not worried about me?” He asked sarcastically. “I could easily capture the two Jews you are hiding, then ship you with them to Dachau.”

She watched him through the mirror as she brushed back her hair. “Yes, you could, but then I wouldn’t be here on Thursday,” she said.

He got up and went into the bathroom. As he passed her, she reached for his bottle of Scotch and poured some into a glass. She looked toward the bathroom as she took one of the ampules from her purse. He was just out of sight…she squeezed the ampule hard, breaking the glass, and the yellowish fluid dripped into the Scotch.

From the bathroom he said again, “See you on Thursday?”

“Yes, captain,” she said, wiping the glass chards off on her skirt. Then she went down the stairs and out the back door.

Walking back to her flat, the impenetrable wall she had constructed started to crumble as she thought about the Scotch. She forced the sense of violation away and by the time she arrived at her apartment, she felt human again. She also felt a sense of triumph. Thinking again about the Scotch, she smiled.

That night, her contact with the escape group visited. He left a Jewess and two young children and took the two elderly Jews away to the next safe house. She wished them good luck and they thanked her. She watched as the contact escorted them across the street and down an alley. The hope that they would survive was all the thanks she needed.

The two children cowered behind their mother as Helga explained where they would hide when the Gestapo arrived.

That night the allied bombing lasted for more than four hours, though none came close to Helga’s flat. She could hear the clatter of tanks moving and men shouting. The smell of diesel invaded her nostrils. Her heart beat fast as she dared to hope.

The next morning at daybreak, small arms fire could be heard. She looked out her window but there was nobody. Several hours later she heard the diesels again, and the distinctive sound of more tanks. Then she saw something she had dared not even dream of: It was the first American tank she had ever seen, and then she knew. She knew it was over.

She grabbed the two children and, with their mother, they walked out into the street, waving and joining others in welcoming the U.S. forces. All the while, Helga hoped against hope she would never have to build another wall.

December 22, 1864

December 22, 1864

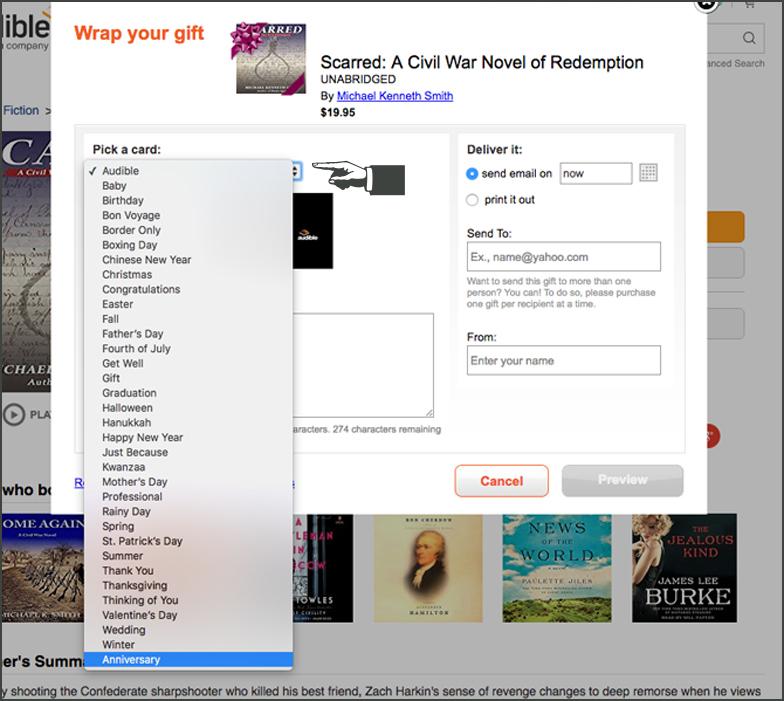

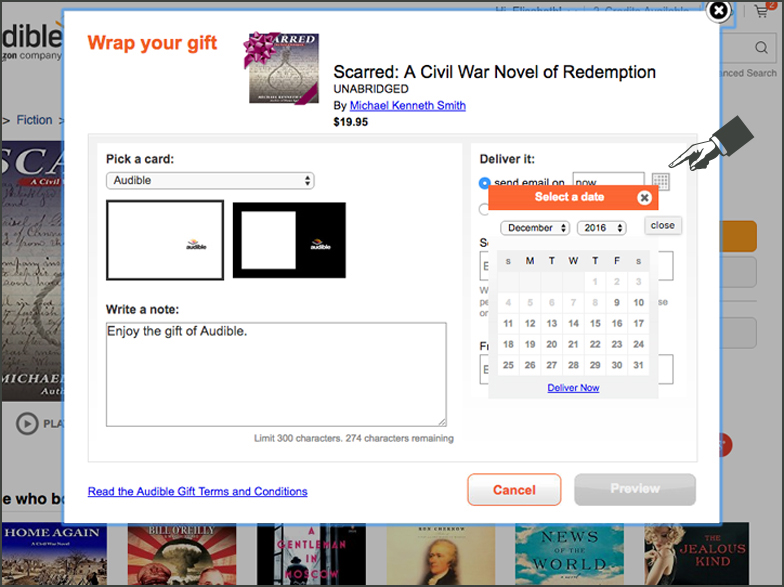

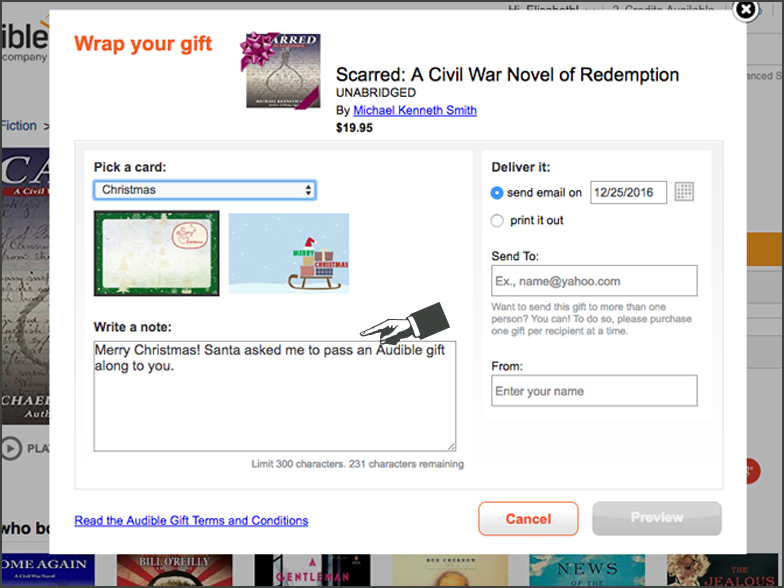

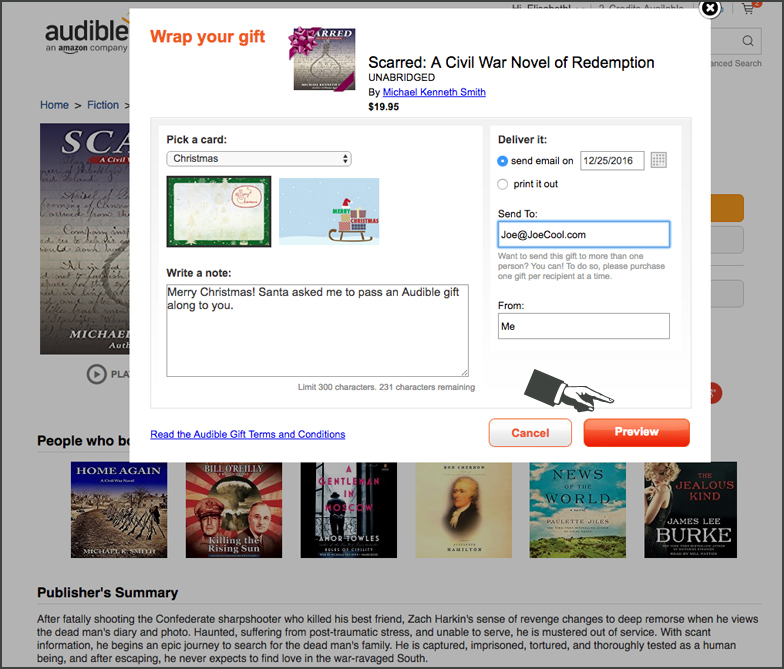

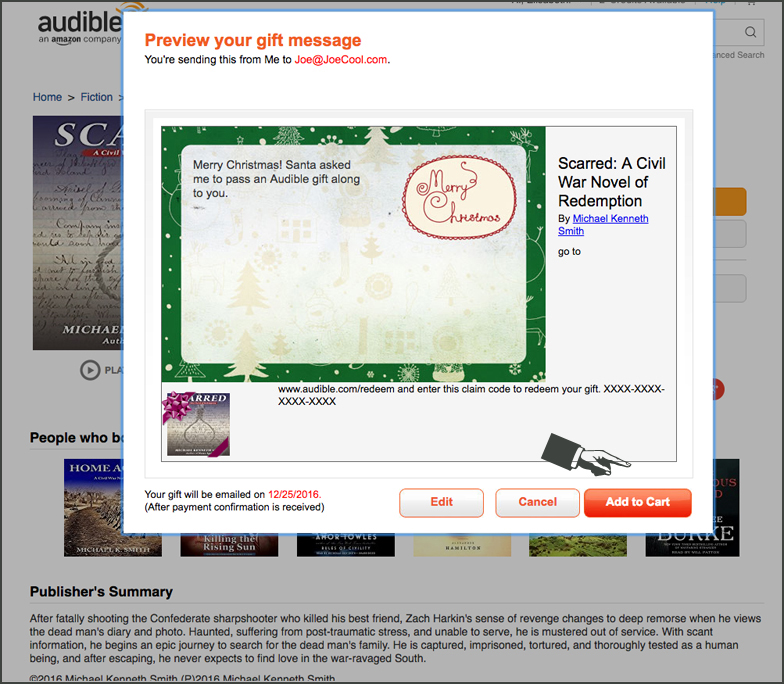

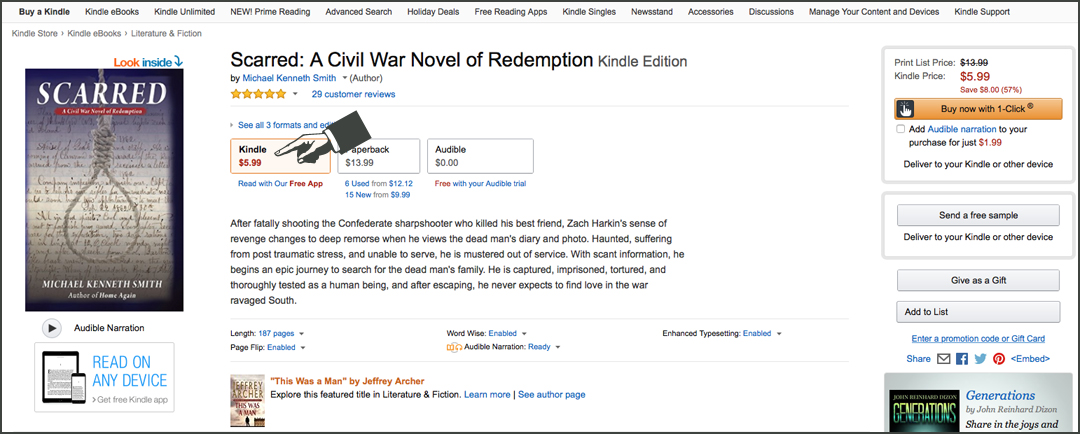

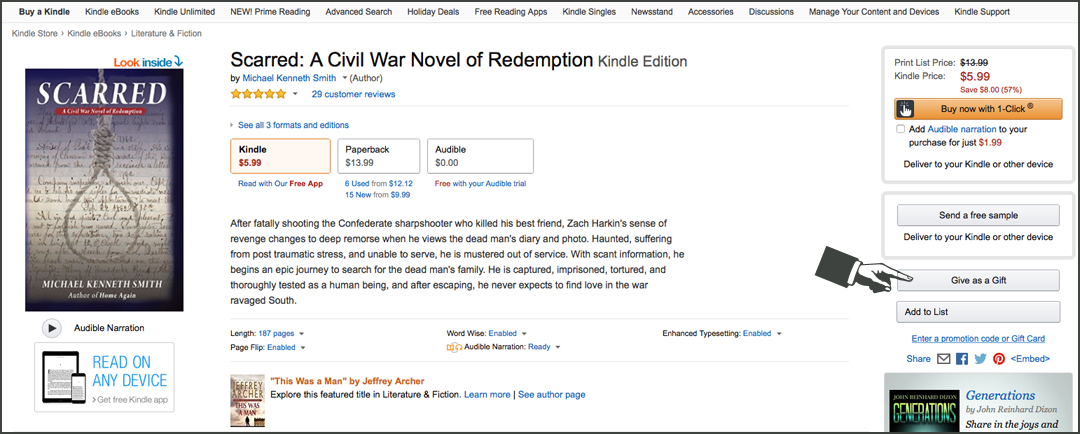

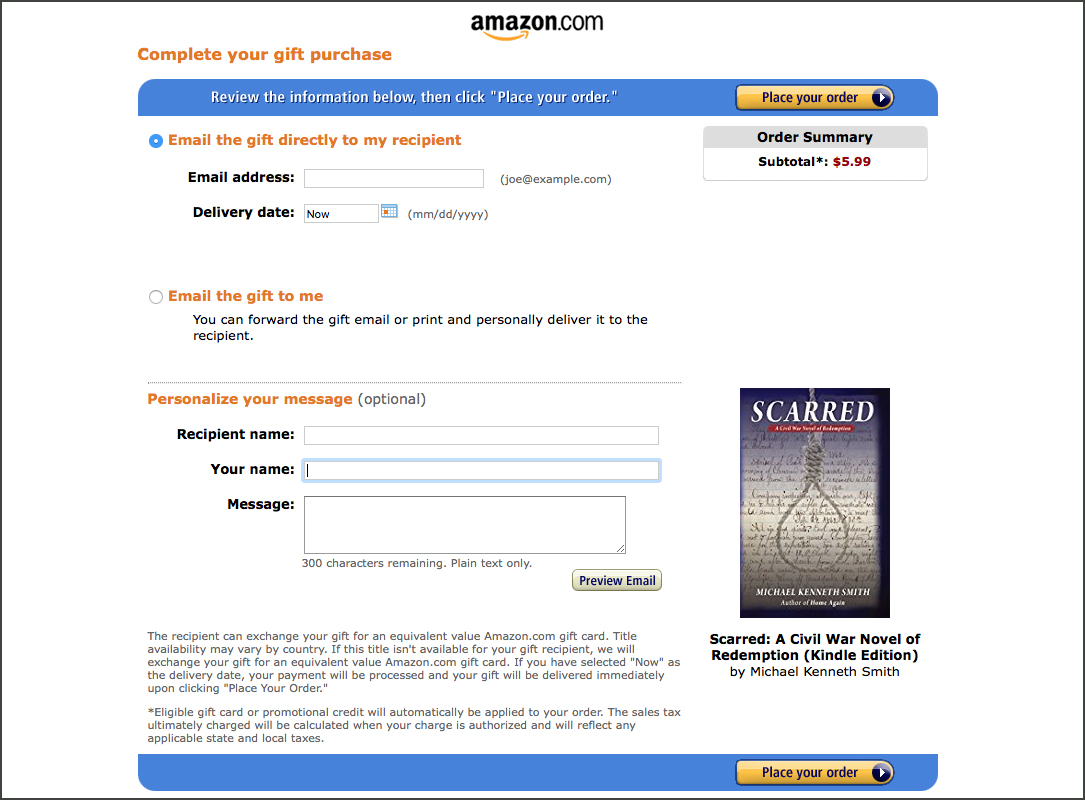

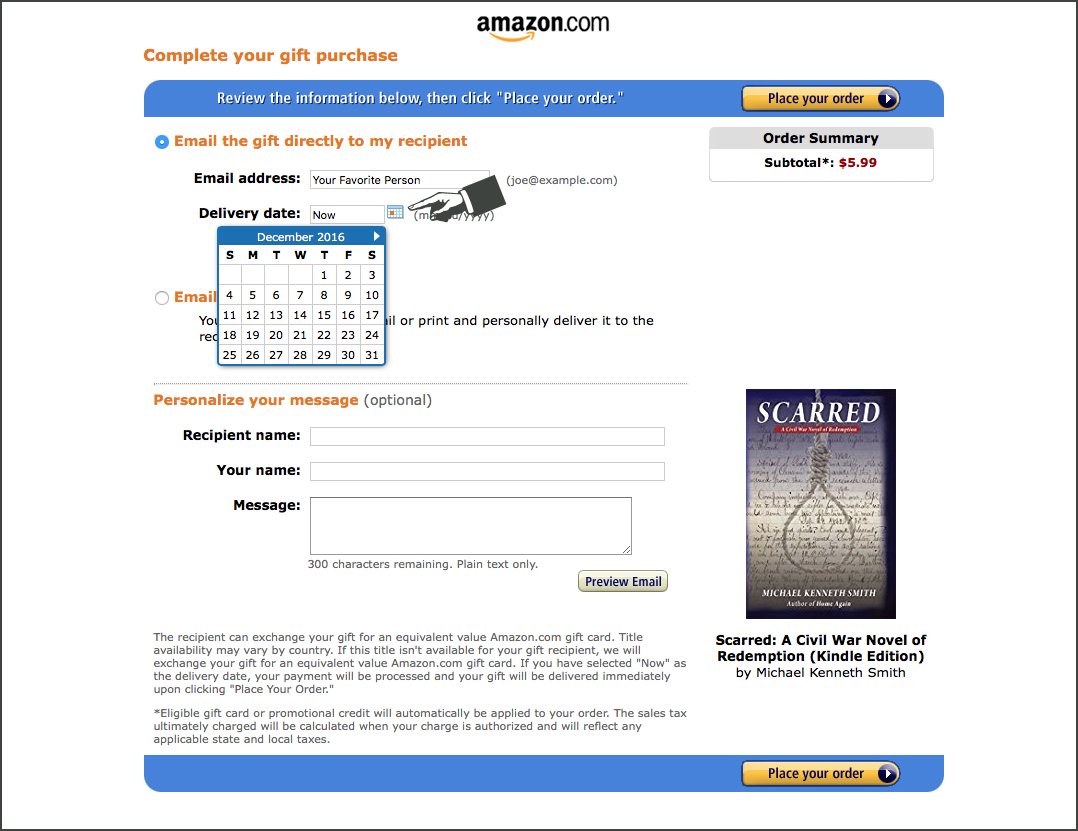

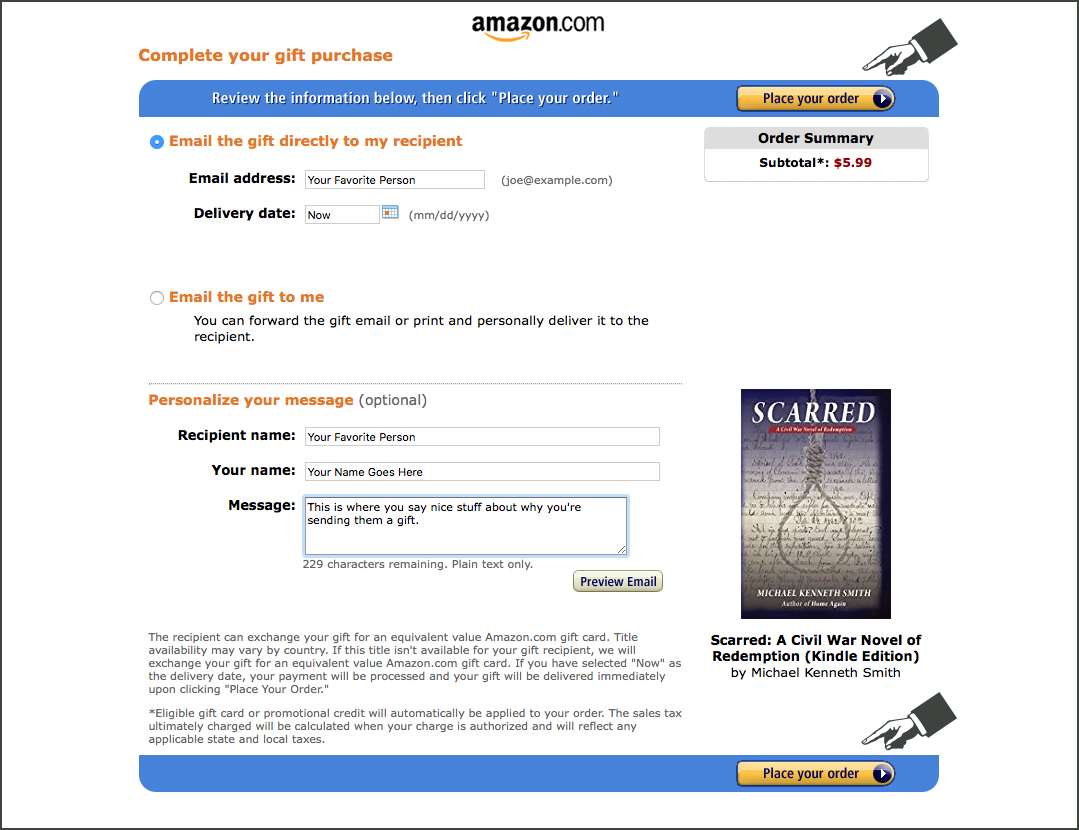

It’s December! (What???) Time to get the holiday decorations out of storage and to start thinking about where you put those boxes, ribbons, and bows. Of course, you could skip some of those be-ribboned boxes this year in favor of giving The World’s Easiest Gift. (No—not cash.) Books! Ebooks, specifically. They’re reasonably priced. Easily personalized. Ready when you are. And shipping is always free! Best of all? You can wrap this one up in five easy steps.

It’s December! (What???) Time to get the holiday decorations out of storage and to start thinking about where you put those boxes, ribbons, and bows. Of course, you could skip some of those be-ribboned boxes this year in favor of giving The World’s Easiest Gift. (No—not cash.) Books! Ebooks, specifically. They’re reasonably priced. Easily personalized. Ready when you are. And shipping is always free! Best of all? You can wrap this one up in five easy steps.

Louis Antoine Godey began publication of

Louis Antoine Godey began publication of  In which we meet Zach, as he sets forth on his journey toward redemption. . . .

In which we meet Zach, as he sets forth on his journey toward redemption. . . . My school was three miles away. Just walk to Cheshire Road, turn left and keep going. I’d take the short cut, which supposedly lessened the distance by a full mile. I would climb the fence in our back yard—the fence that kept our two mares from being bred by the neighbor’s stallion. Then, once over the fence, I could walk diagonally toward Pritchard’s place, over two more fences, a small creek, and…wha-la, the school play ground.

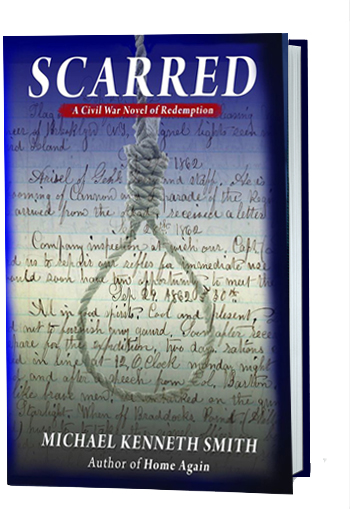

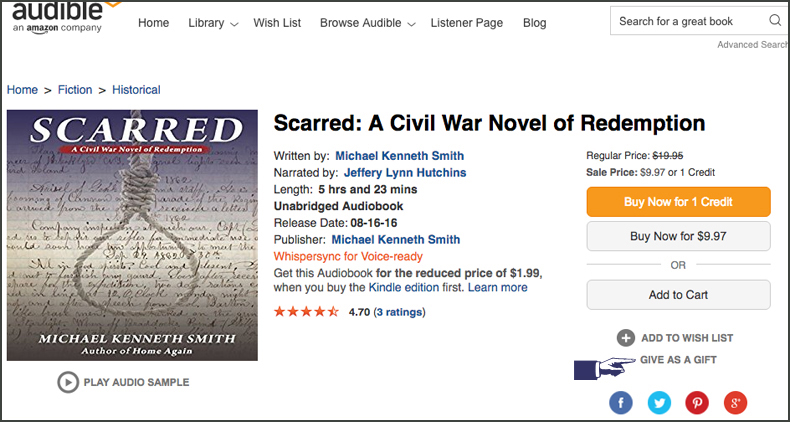

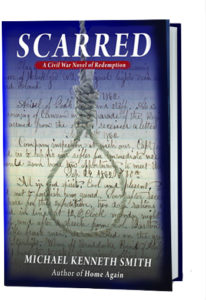

My school was three miles away. Just walk to Cheshire Road, turn left and keep going. I’d take the short cut, which supposedly lessened the distance by a full mile. I would climb the fence in our back yard—the fence that kept our two mares from being bred by the neighbor’s stallion. Then, once over the fence, I could walk diagonally toward Pritchard’s place, over two more fences, a small creek, and…wha-la, the school play ground. A battle scene in a novel can be a very powerful and important element that, if done correctly, will define your protagonist—which is why we all need novel writing advice on how to adequately accomplish write one. Your protagonist might distinguish himself/herself in such a way that the reader gains intimate knowledge into his/her psyche while carrying the story forward. The author can use the natural tension of battle and a soldier’s fear to demonstrate the protagonist’s true character whether he/she be a hero, antihero, or just learning an important lesson. An example of this revelation of character is in my first book, Home Again.Luke, the young teenage protagonist, goes off to war. At the Battle of Shiloh, we learn he has a strong compassion for the wounded, his compassion is manifested by the way he cares for victims. For the rest of the novel, the reader knows how he will react in similar situations. In a way, his actions in battle defined him and foreshadow the themes of my second novel,

A battle scene in a novel can be a very powerful and important element that, if done correctly, will define your protagonist—which is why we all need novel writing advice on how to adequately accomplish write one. Your protagonist might distinguish himself/herself in such a way that the reader gains intimate knowledge into his/her psyche while carrying the story forward. The author can use the natural tension of battle and a soldier’s fear to demonstrate the protagonist’s true character whether he/she be a hero, antihero, or just learning an important lesson. An example of this revelation of character is in my first book, Home Again.Luke, the young teenage protagonist, goes off to war. At the Battle of Shiloh, we learn he has a strong compassion for the wounded, his compassion is manifested by the way he cares for victims. For the rest of the novel, the reader knows how he will react in similar situations. In a way, his actions in battle defined him and foreshadow the themes of my second novel,