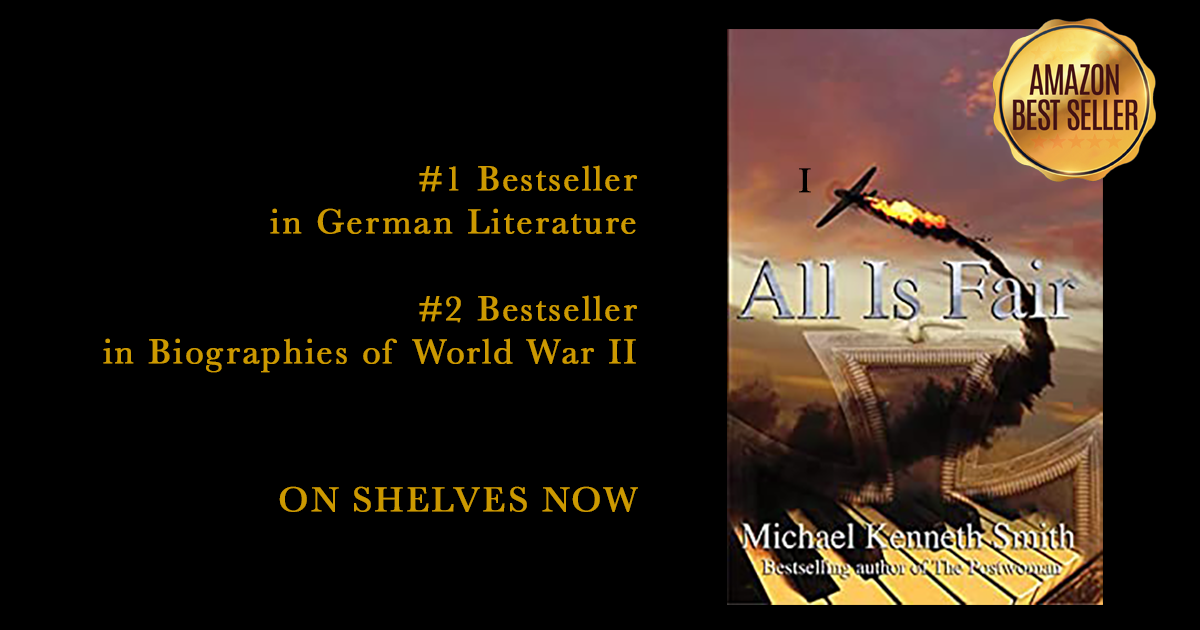

I’m delighted to share my latest novel, All Is Fair, has reached Top Three Bestseller status in the categories of German Literature (#1) and Biographies of World War II (#2).

Learn more here.

I’m delighted to share my latest novel, All Is Fair, has reached Top Three Bestseller status in the categories of German Literature (#1) and Biographies of World War II (#2).

Learn more here.

Submissions for the Michael K. Smith Novel Fellowship for 2022 are now open!

Spend an immersive two-and-a-half days, one-on-one, with renowned editor Greg Michalson at the Porches Writing Retreat.

For information on this and other fellowships as well as submission requirements, please visit Porches Writing Retreat.

It was dark. The only light came in through a little hole on the side of my little house. Out there somewhere where lights, not just any lights, but blue, green and red lights. And they were blinking. On, off, on off. Like some unseen metronome marking the beat to some unheard melody. But the sound, or lack of it, is what startled me most. If there was such a thing as a deafening silence, this was it. Maybe I was being punished I thought. After-all, my life had been anything but exemplary. I had not achieved anything in my life besides making it to my three month birthday.

It was dark. The only light came in through a little hole on the side of my little house. Out there somewhere where lights, not just any lights, but blue, green and red lights. And they were blinking. On, off, on off. Like some unseen metronome marking the beat to some unheard melody. But the sound, or lack of it, is what startled me most. If there was such a thing as a deafening silence, this was it. Maybe I was being punished I thought. After-all, my life had been anything but exemplary. I had not achieved anything in my life besides making it to my three month birthday.

I started to doze off again when I heard muffled footsteps. Very faint at first then getting closer. Must be coming down the steps I pondered. Then the footsteps came very close and stopped. Several moments later, I felt my little house was being lifted up into the air. Then everything started shaking light some violent earthquake. So much so, my teeth shattered.

Then it happened. A very loud shout. “Get back to bed, NOW!” I was suddenly dropped to the floor and the muffled steps went back up the stairs and nothing. A stone cold quiet. If I thought it was very quiet before, this was even quieter.

Several hours later, I woke with a clatter. Voices. Happy voices and I wondered what was the matter. I was picked up again and this time I heard paper ripping and my comfortable little cocoon was torn open. Light. Bright light. I blinked my eyes, looked up and saw this little girl. She had curly blond hair and a very surprised look on her face. I didn’t know what I did to deserve it, but she seemed very happy to see me. I couldn’t think of anything else to do but lick her face. It must have been the right because she giggled and petted me over and over. I had the distinct feeling I was going to be very happy on this wonderful day.

December 22, 1864

December 22, 1864

A thin layer of clouds glowed silver and the nearly full moon provided enough light to see the opposing earthworks to the west. Goma vigorously rubbed the scars on his wrists trying to increase circulation. The light wind was from the west and he could smell the last burning embers from dozens of fires. The cool Virginia soil tried to steal what little body heat he had left.

Goma looked back toward his own lines and hoped the replacement pickets would arrive soon. This was Goma’s first time on picket duty, and he didn’t like being alone.

Almost three-hundred yards separated the Union and Confederate main lines just outside of Petersburg, and because the distance was quite large, both sides had additional sparely manned buffer picket lines inside their regular pickets and only about fifty yards apart. No largescale fighting normally occurred during the winter months and both sides dealt with shortages and boredom. The South, with their supply lines under constant siege, suffered from food shortage much more than the North.

“Hey, Yankee, can you hear me?” Goma turned abruptly toward the Rebel line. “Hey, Yankee,” the voice repeated in a heavy southern draw. “You ‘bout ready to give up and go home?”

Goma hesitated. Then he said, “Neva’ happin, Johnny.”

A brief silence. “You a darkie?”

Just then Goma’s replacement crawled into the trench and Goma crawled back to his lines. When he got to his tent, he lay down to sleep, but he kept thinking about the voice. Something was very familiar.

Only a few short months ago, Goma was a groom at a plantation near Jonesboro, Georgia. His father’s father had been brought across the ocean and was sold to a farmer near Savanah where Goma was born. When Goma was twenty, he was sold to John McCord, the master of Stately Oaks Plantation near Jonesboro, Georgia. While John McCord was a kind slave master, his son, Elijah, in trying to impress his father, treated Goma and others harshly. Whenever Elijah found the least little fault with Goma’s work, he would frequently wield a whip or lock Goma away.

In early September, 1864, when Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee drove out all the belligerent Confederates, all the slaves were freed. Not knowing what to do, Goma followed Sherman’s army and was shortly inducted into the United States Colored Troops and became part of XXV Corps of the Army of the Potomac under General Edward Hines. The U.S.C.T. troops were extensively deployed in the Siege of Petersburg.

The next morning, Goma sat around the breakfast fire with several of his new friends, all ex-slaves. He told them he suspected the Rebel voice he had heard in the night might be Elijah, his old nemesis. They asked him how badly he had been treated and Goma showed the scars on his back. None of his friends had been treated that way and the discussion became heated.

“We got ourselves the big equalizer,” one said in a heavy accent picking up his rifle. “Only one way to settle this.”

“How would we do it?” Another asked. “We can’t just walk over there and shoot him.”

“We could crawl over the next cloudy night. Shit. Nobody would miss the dirty bastard,” the first one said. “What do you think, Goma? You’re the one he treated so bad.”

Goma was quiet for a moment, then said, “You know, the first few times he beat me, I had this rage inside. It kept me going. I hated that man more than I could hate anything.” He waited a moment as if to choose the right words. “But then, after a while, I just started to feel sorry for him.”

“How could you feel sorry for a man who is beating you? That just sounds impossible, Goma. You gotta be crazy,” the first said.

“Yeah, I know it sounds crazy and maybe it is,” Goma said, “but I feel like if we shoot him, we might be worse than him.”

“You can’t get worse than him, Goma, that man is the worst there is. He’s the bottom of the barrel. He’s the devil himself.”

Slowly, the conversation died down, and the men all started talking about Christmas and how they wished they were away from all the killing, the war. They wanted to get on with their lives even though nobody had any idea what the future would bring after the war.

The next day, Goma was told he would again be on picket duty that night. He had hoped to celebrate Christmas eve with his friends, but he was used to being disappointed, and he accepted it without comment. Most soldiers only thought about three things: food, shelter and home. Goma had no home except where he slept each night.

The entrenched Union line extended nearly thirteen miles from end to end with well over one hundred thousand soldiers living in ramshackle shelters. Some were tents with the sides built up with dirt to keep the wind out. Others were wooden structures made of logs. Some had stoves inside. The soldiers were given total freedom to build whatever they wished to keep them dry and warm.

Since early morning, wagons loaded with special Christmas food were arriving from the north. Turkeys, chickens, cakes and pies, all ready to eat. Goma and his friends were able to get a whole turkey and a couple pies. After dinner, different groups broke into song, however, as evening approached, Goma reported to the duty officer and prepared to crawl out to the first line of pickets. He carried his Springfield musket, ammunition pouch and a knapsack containing a small apple pie.

At the appointed time, just after dark, he started to crawl to the main picket line. The early night sky was heavy with dark clouds and he could have walked because of the low visibility, but Goma felt safer crawling. The area between the battle siege lines was grassless and he could feel the hard dirt clods through his foraging jacket. By the time he got to the line of picket trenches, the other replacements had already arrived. He was informed he was assigned the outer picket line from around 12:00 midnight to 2:00 am.

The area between the two outer pickets was called ‘no man’s land,’ and as the moon peeked through the breaks in the clouds, it looked like the gates of Hell, filled with shell holes, old trench emplacements and scattered battle debris. Goma wound his way to the ditch where he would spend the first hours of Christmas Day. After relieving the prior sentry, he settled in, sitting on part of a cannon caisson that had been destroyed earlier. Every few minutes he would peer above the ground toward the enemy lines to verify what he suspected: nothing would happen on Christmas. He thought about the pie and his mouth watered.

“Hey, Yankee, are you there?” The voice was clear as a bell. The same voice as before. “Its Christmas. Are you Northerners going back north where you belong?”

“No chance of that, Johnnie,” Goma said.

“I remember your voice, you’re a god damned Darkie, aren’t ya.”

Goma now knew who the man was. He was Elijah. For some reason, he always used the word ‘Darkie’. Like it was his invention or something. Maybe it made him feel like he had some control over the English language.

“You bet your sweet ass I’m a Darkie, and this Darkie knows what a cruel slave master you really are. I’ve got the scars to prove it.”

Elijah said nothing for a few moments. “Goma? Goma?—You’re Goma! What the hell are you doing out here. My God—Goma.” Elijah was silent for a few minutes. In a more measured voice he said. “You still belong to me. You are my property, although you were the laziest goddamned slave I ever owned.”

“I’m a free man,” Goma said in a firm voice.

“Free, my ass. I can see that I didn’t whip you near enough. I loved seeing my whip rip open your skin. The blood oozing out. Hearing your sorry ass whimpering. Yep, I should have done more of it. Would’ve made a man out of you.”

Goma just smiled. He always knew that when Elijah bragged about something, it was his way of trying to convince himself he was important. “I hear you Johnnies aren’t getting much to eat. That true? I hear you are near starving.”

“We get plenty to eat,” Elijah said, “I get so full, sometimes I have trouble walking.”

“Good to hear, Johnnie, guess that means you don’t want any of my apple pie.”

“You got apple pie?—apple pie?” Elijah said in disbelief.

“Apples covered with brown sugar and pecans. Yep.”

“I don’t believe it. Not for one minute.”

Goma didn’t answer. He waited.

“Apple pie?” Elijah asked again.

Ten minutes later, Goma had made up his mind. He crawled up over the top of his ditch and inched his way toward Elijah’s position. The moonlight was obscured by passing clouds. When he got to the hole Elijah was in, Elijah put the barrel end of his musket to Goma’s forehead. “You’re dumber than I ever imagined,” Elijah said. “Now you’re gonna die.”

Goma reached into his knapsack, pulled out the pie and handed it to Elijah. Elijah first stared at the pie, then at Goma, his mouth open in wonderment.

“Merry Christmas,” Goma said and he crawled back to his own trench.

A short story by Michael Kenneth Smith

The following is excerpted from In the Shadow of Gold—which Kirkus calls a “high-stakes, well-paced adventure saga.”

Chapter 1

June, 2020

The sound of small glacial stones hitting the undercarriage of the speeding red Jeep Rubicon ended when the road became paved, marking the beginning of the Arvin property. Minutes later, Jonas Arvin reached under the dash and pressed a button, and the tall, wrought-iron gates opened, splitting the name Cherry Side Arboretum and revealing the tree-lined driveway that meandered up the hill. Jonas’s cell phone vibrated, and the Jeep’s GPS screen lit up: Klinger is on. Jonas hit the talk button. “On property. Three minutes.”

The Jeep wove its way upwards, the rows of cherry trees flashing by on one side with mature pin oak, red maple, white birch, and fir trees flanking the other. A Black worker dressed in a gray Cherry Side uniform waved to Jonas as he steered a gang reel mower across the grass, and Jonas waved back. Soon an American flag came into view, then the state flag of Michigan just below it as Jonas neared the top of the mountain and his Cherry Side home. After parking out front, Jonas hurried up the steps to the three-story log mansion. The maid, Maggie, opened the front door.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Arvin,” she said. “Your call is waiting in the office.”

“Thank you, Maggie.” Jonas bounded up the floating log stairs two at a time and entered a huge room with a twelve-foot-square drop-down screen that showed a man in a suit standing with his arms folded, smiling. On the opposite wall, behind the desk, hung a huge oil painting of Robert E. Lee riding his horse, Traveller.

Jonas threw his Kalamazoo Giants baseball cap onto a leather sofa, leaned against the front of his desk facing the screen, and took a deep breath. “Okay, Klinger, what do you have?”

“We can schedule this another time, if you’re busy,” Klinger said.

Jonas had been at the park coaching his Little League team, and he’d left practice early in order to take this call.

“No,” Jonas said. “Tell me what you have.”

“You directed me to try to find the original source of the Arvin fortune. I must admit the trail, if there is one, is very cold. As best we can tell, your wealth was created in the mid-to-late 1880s, but the seed capital was probably amassed closer to the time of the Civil War. One of the great mysteries of that war that has remained unsolved all these years is what happened to the Confederate treasure after the war was over. Granted, it’s a long shot. Shall I continue to investigate?”

Jonas glanced at a large, framed daguerreotype of Abe Lincoln in his early days as a local politician back in Springfield. The image was unlike most other Lincoln portraits in that it featured Abe’s face sans beard.

“Absolutely” Jonas said. “What else do you have?”

“Nothing much. Do you want a brief financial of last month’s performance?”

“Sure, fire away. Make it quick.”

“Domestic holdings are thriving. The depreciation of the yuan due to trade policies is causing us problems. Europe and the Middle East are fine. Net, net, we held our own last month with our net assets still holding at $3.25 billion, plus or minus.”

“Always add the ‘plus or minus,’ huh? You’re the best at CYA I know of.”

“You call it CYA,” Klinger said. “I call it a moving target.”

“Well, you’re doing a good job. You’ve filled your father’s shoes very well.”

Jonas’s dad had told him about how it used to be. Nip and tuck. When Klinger’s father had finally convinced Jonas’s grandfather to sell his old Rust Belt stocks and buy tech, that was when the fortune had really started to grow.

“Thank you, sir,” Klinger said as Jonas’s wife, Francie, came into the room. She sidled next to Jonas, putting her arm around him and facing the screen.

“Hi, Klinger,” she said.

“Hello, Mrs. Arvin. You’re looking particularly well today.”

“Still full of it, I see,” she said. Then, turning to Jonas, she added, “You promised me lunch at the club.”

“I can take a hint,” Klinger said. “I’m outta here.” He pressed a button and the screen went blank.

Francie yelled for Maggie, their maid, to bring her purse. A moment later, Maggie was there with a powder blue Hermes bag. Francie took the bag and waited for Jonas, who stood staring at the image of Lincoln again.

“Do you think the Civil War is the key to this whole thing?” Jonas asked.

“Key to what?” Francie said.

Something about the picture held Jonas’s attention. The young man in the photo, dressed as would a young attorney, had governed the United States when the country was nearly split in half and embroiled in a war that would ultimately claim more than 600,000 young men, almost fifty percent more than died in World War II. That man, if he would have lived to tell about it, might have known something about the treasure.

“Come on Jonas,” Francie said, walking out the door. “I’m hungry.”

Chapter 2

April 1861

A wave swept over the bow of the brigantine-rigged steamer Yorktown as she began a turn that would take her past Fort Monroe through Hampton Roads, up the James, and on to Richmond. The steamer, now running perpendicular to the north wind and waves, rolled back and forth as her side wheels alternately struggled for purchase in the turbulent sea.

Crewman Yancey Arvindale clutched the port rail, trying to keep his eyes on the horizon while wishing he were dead. Another wave broke over the forecastle and sprayed Yancey, further adding to his misery. For the past three days, he had been seasick, and the change in rhythm of the ship from a following sea to a cross-wind roll caused him to wretch again. He hadn’t eaten since their departure from New York City, and the only thing that came up was yellow bile, some of which stained his white blouse. Of the several hundred people on the ship, maybe a few had been sick the first day of the voyage, but at this point he was the only one still on deck and in need of a bucket.

The ship’s captain walked by and stopped. He stared at his son. “Sit in the center of the ship, son, and always look forward,” he said.

Yancey wretched again.

“I don’t have a sailor on board who hasn’t gone through this. You’ll be just fine.”

“This is my third round trip,” Yancey said, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. “I’m never going to be a sailor. I don’t want to be.”

“Nonsense, son. We’re a family of sailors. It’s in our blood. You’ll get the hang of it.” The captain walked back toward his helm. Even though the ship was rolling, his steps were even, as though he had been born on the deck of a ship in a stormy sea.

Yancey eyed him with contempt, but his anger was short lived, as his nausea returned and he dry wretched again. His legs felt weak, so he sat down, leaning against the forward mast, always keeping his eyes on the horizon. He thought about his three brothers, who had graduated from the United States Naval Academy. Each had displayed their father’s passion for the sea. They loved it. Why was he the exception? It didn’t help that he was five years younger than his next oldest brother. Yancey had always wondered if he might have been a mistake. He also knew his father had always wanted a daughter, and he felt both parents treated him with less respect and trust than his siblings. Until his brothers went to the Academy, their father gave them allowances for doing various odd jobs, but never Yancey, even though he did the same jobs. In the back of his mind, Yancey desperately wanted to prove himself, but it was clear he wasn’t going to do so as a sailor.

As the ship churned on and became alee of Fort Monroe, she found better waters, and the ride smoothed. Passengers came out of their cabins and peered over to starboard at the huge fort. Only two weeks prior, Virginia had seceded from the Union, and most on board wondered if the fort would revert to Virginia or stay occupied by the North. Yancey thought about what would happen if there was a war between the North and South. His classmates were always talking about what it would be like, endlessly boasting of how they would slay the enemy and become heroes. Yancey wondered how he himself would perform under fire. Would he be calm and shoot straight, or would he get up and run? He hoped he never had to find out.

The water flattened as the ship sailed past Hampton Roads and turned to the northwest. Yancey tried to stand. He felt weak, and his stomach felt like it had been used as a punching bag. Holding onto the mast, he felt a welcome, cool land breeze on his face that reminded him his clothes were wet from perspiration and salt spray. He began to shiver as he thought about what he would do when they docked in Richmond. He felt a gnawing emptiness in his stomach, but he couldn’t bear to think of eating. He knew it would take at least another day for his body to overcome the seasickness.

It was late afternoon when the Yorktown shuddered as the captain reversed one wheel and accelerated the other, causing the big ship to spin around to face downriver as she neared her Rocketts mooring. Then both wheels went into neutral, the momentum of the ship subsided, and she softly kissed her berth on the dock. Yancey suspected none of the passengers appreciated the precision control the captain had just displayed. It was a talent few captains had, and one he knew his brothers were capable of developing. But not him. He just wanted off.

As soon as the first of two gangplanks were lowered, a tall man followed by four irregularly uniformed soldiers boarded the ship. The officious-looking leader, wearing a stovepipe hat, walked to the center of the forward deck with two of the soldiers. The other two blocked anybody from disembarking. The man with the stovepipe hat asked the captain of the ship to come forward. Yancey’s father, appearing to know what was transpiring, walked up and stood beside him. The ship’s halyard thumped against the mast in an irregular beat.

The leader unrolled a sheet of paper, donned a pair of spectacles, and read aloud. “Under the authority of the Commonwealth of Virginia, this ship is being confiscated and no longer belongs to the Old Dominion Shipping Company. All passengers shall take their belongings and disembark. The ship’s crew is no longer required and shall disembark after all the passengers have left. Captain Arvindale, please report to me.”

Yancey was elated. No more trips to New York. No more long days of seasickness. Maybe now that Virginia had seceded, his father would forget about sending him to the Naval Academy. He watched his father and the tall speaker shake hands and pat each other on the back. He wondered why Virginia would confiscate the Yorktown. She was not a fighting ship. What possible value would she be?

The lady passengers used their parasols to shield the late-afternoon sun from their faces as they walked the wide gangplank onto the dock. The men, most of whom had had business in New York, lit up cigars while disembarking. Yancey had always wondered why the men wanted a cigar whenever their ship arrived at their destination port. The passengers were followed by porters who handled baggage, including large trunks loaded with purchases from the big city. From his position near the mast, Yancey could see the gangplank sag from the excessive weight. One muscular negro man was carrying a particularly large steamer trunk on his back when he tripped on a tread board, nearly causing the trunk to slide into the muddy water. Another crew member and Yancey, partially recovered from his nausea, rushed to help the big man. The crew member got to the gangplank just behind Yancey and pushed him aside, causing Yancey to grasp the ropes to keep from falling in. “Let a man handle this,” the crew member said in a low voice. “You go back and hide under your father’s shadow.”

Yancey felt his face turn red, his anger rising like lava inside a volcano pushing hard on a thin mantle—one that had broken many times before. Regaining his balance, Yancey rushed at the crew member and rammed his shoulder into the man’s back with as much force as he could muster. The crewman lost his grip on the trunk, which started to slide off the gangplank. As the crewman tried to grab it, he and the trunk fell into the water near the dock. The trunk’s lid came open on impact, spilling its contents into the river. A broad brimmed hat floated on the water’s surface with its ostrich feather like a sail. A white body corset wafted nearby like two large snowballs bobbing in the light breeze.

The collision with the crewman had left Yancey prone on the gangplank. As the big porter looked on in shock, Yancey got up, ignoring the crewman in the water who was cursing and shaking his fist, and walked off the ramp onto the pier, where he picked his way through the throng of onlookers.

His home was on Grace Street. By the time he was halfway there, his temper had settled, and the reality of what he had done started to sink in. Yancey hoped the incident would be forgotten in the turmoil caused by the seizure of the Yorktown. The previous year, when he had turned seventeen, his father had stopped spanking him. His punishments thereafter included being locked in his room or confined to the yard. This time, however, might be different. He had never caused much damage before. The worst thing he’d done was to punch a classmate, causing his eye to swell shut. Yancey had never seen an eye swell over before, and he thought he might have permanently ruined the boy’s sight. The school principal, who was a friend of his father’s, sent him home. When Yancey’s father confronted him, he told the truth. He told him the boy had made fun of him and explained he was further embarrassed because the whole incident took place in front of a girl he was fond of. Three whacks. That was all. After the punishment, Yancey thought it over and decided it had been worth it, and he would probably do it again. But down deep, Yancey knew his temper would get him into trouble someday, and he vowed to control it, although he had made the same vow before.

My other novels can be found here.

I’ve been fortunate to have a number of media and bookstore events for the publication of THE THIN GRAY LINE—and it’s been a lot of fun! Here’s a clip from a recent radio show I did with station WEOL.

“… a nonfiction book on the history of the Civil War will tell you what happened…a book such as THE THIN GRAY LINE will tell you how it felt.”

And since we’re in “listening mode”, this would likely be a good time to mention THE THIN GRAY LINE is also available as an audiobook through audible.com.

When writing my first book, Home Again, the idea of writing a trilogy never entered my mind. The story was about two young boys who quickly became men. Both from Tennessee, each signed up to join the war, Luke for the South and Zach for the North. Near the end of the war, each of the young men returned home damaged: Zach had post-traumatic stress and Luke was near death from his wounds.

When writing my first book, Home Again, the idea of writing a trilogy never entered my mind. The story was about two young boys who quickly became men. Both from Tennessee, each signed up to join the war, Luke for the South and Zach for the North. Near the end of the war, each of the young men returned home damaged: Zach had post-traumatic stress and Luke was near death from his wounds.

After its publication, many readers of Home Again asked me what happened to Zach. They were curious to know more about how he handled his malady, and so the second book, Scarred, explained in great detail how he faced his demons down and ultimately freed himself from his psychological nightmare. Scarred addressed the trauma many soldiers must have felt before the days when PTSD was diagnosed.

I also learned, in the aftermath of Home Again‘s publication, that readers didn’t want Luke to die—in spite of his near-death status. I must admit, I didn’t intend for him to survive his wounds. But then I started to think, “What if he had survived?” And “What would have happened to him?”

The third book in this trilogy of sorts, The Thin Gray Line, follows Luke who survives a leg amputation and becomes addicted to opioids. He fears rejection by his sweetheart Carol and is constantly trying to prove his worthiness to his father—though it is unclear whether his father is even still alive. In his coming-of-age, Luke learns a thing or two, and, in the end, must make a decision to follow his heart or follow his conscience. He ultimately gains redemption in a place he never suspected.

While each book stands on its own, the combined life stories of these two men describe the brutal reality of our Civil War during in which over six hundred thousand men lost their lives.

Click for more on Home Again, Scarred, and The Thing Gray Line.

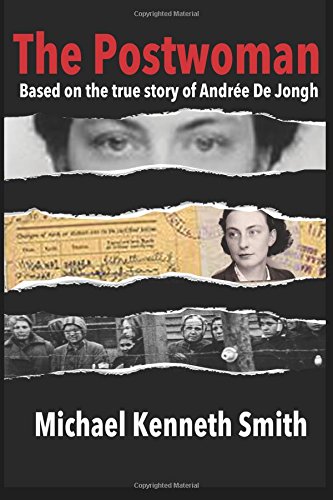

Delighted to share The Postwoman has achieved “Top 5” Category Bestseller on Kindle!

Learn more HERE.

My first two novels were about fictitious men in the Civil War and both followed a vague timeline scripted by history. The story of Andrée (Dedee) de Jongh, on the other hand, offered a chance to write something different. Dedee’s story is about a real person, and while little was written about her life in WW2, the parameters of writing changed dramatically. Writing about a real person meant that I had to be true to her defined character in every word I wrote about her—as opposed to writing about a fictitious person which would allow me to improvise and suit the character to the story.

In the first half of the book, readers find out who Dedee really was. She was a true Belgian patriot and passionately despised the German’s for invading and occupying her country. Time and time again, she outwits her German protagonists with cunning preciseness. By researching published journals, her early participation in the war and the methods she used to create the war’s most successful escape line, could be pieced together. While private conversations and specific day-to-day activities were not recorded, her general location during the early part of the war could be ascertained through reference books and documents, the latter of which were available online.

Composing this part of her story required a different discipline than I had been used to. The timeline had to dance to the beat of history as did her accomplishments. My writing felt constricted. Early drafts were stilted and awkward. I couldn’t let my imagination work as I normally do, and as a result, the product seemed unnatural. For example, when Dedee sleeps with her four evaders early in the book, I wanted to make the scene much more dramatic, however, several research sources had recorded that actual scene in books written about others who had shared her bed. I had to tell it the way it actually happened. One reviewer called the scene ‘contrived’ and I can see the point, but that was truly the way it happened. Over time, as I drew to better understand who Dedee really was, composing her early participation in the war became easier. The first half took me six months to draft after all the research was completed.

In the second half of the book, Dedee has been captured and spends the rest of the war in prisons and concentration camps. Because of the paucity of information from inside the camps, very little was known of her activities. Many journals have recorded the concentration camp lives of survivors, so her activities followed what might have happened based on those stories. As a result of no longer being constricted to a specific timeline, I felt much freer to improvise which, for me, allowed me to better demonstrate her character. It was like walking out of a small closet into a large room. For instance, when Dedee is working in a Seiman’s factory near the camp, she outsmarts the Germans by making defective parts right under the their noses without them even suspecting. I drafted the second half in less than thirty days.

When I started my research for this book, I felt like I was infringing on Dedee’s life. She was a very private person who eschewed the spotlight. I was an outsider trying to expose her story. As I learned more and more about this unbelievable woman, I fell in love with her. Her story needed to be told. I’ve read the last twenty pages many, many times and I still cannot read it with a dry eye because I feel so close to her. I hope readers of The Postwoman come away with the same feeling.

Click here to learn more about The Postwoman, based on the true story of Andrée de Jongh.

Having learned that Lynne Olson was coming to our community to talk about her then latest book, Citizens of London, I read it and found the book captivating. After her lecture, we had dinner and I asked her about her brief reference to Belgian, Andrée de Jongh, a World War II resistance fighter. She said a comprehensive book on her life in the war had never been written and she hoped somebody would tell de Jongh’s very compelling story. Having already written two American Civil War novels myself, the concept of writing about WWII really piqued my interest. When I expressed a certain curiosity about de Jongh, Ms. Olson pointed her finger at me and said that I should write her story, and if I did she would forward some research she had already written about her.

Having learned that Lynne Olson was coming to our community to talk about her then latest book, Citizens of London, I read it and found the book captivating. After her lecture, we had dinner and I asked her about her brief reference to Belgian, Andrée de Jongh, a World War II resistance fighter. She said a comprehensive book on her life in the war had never been written and she hoped somebody would tell de Jongh’s very compelling story. Having already written two American Civil War novels myself, the concept of writing about WWII really piqued my interest. When I expressed a certain curiosity about de Jongh, Ms. Olson pointed her finger at me and said that I should write her story, and if I did she would forward some research she had already written about her.

A few days later, I received a packet from Lynne with the research she had written and I was hooked. Because so little of her life was actually documented, the book would have to be a novel which would give me the opportunity—and the challenge—to make her life come alive while following her known timeline and experiences. Some say that historical nonfiction will tell the reader when and what happens and a historical novelist (fiction) will tell the reader how it felt. I wanted to tell the story of Andrée de Jongh (aka Dedee) from her perspective and write about not only her exploits, but her personal experience.

From a research perspective, I am very comfortable writing about the Civil War . . . switching to the European Theater of WWII was a challenge, though my research methods remained the same. When writing about the Civil War, I have a general concept of timelines and main events, and while I had timelines and main events, WWII also required constant referrals to written texts to make sure I had all my facts straight. I always try to make my historical novels dance to the beat of actual timelines and events.

The protagonists in my first two novels (Home Again and Scarred) were men and, as a man, I could easily relate whether it was a love scene, action scene or any other. Andrée de Jongh was a woman—a young, attractive and very driven woman—who dealt with very strong men, whether they were Nazis, RAF fliers, Luftwaffe captains or concentration camp guards. Detailing the constant conflict between Ms. de Jongh and these powerful personalities required a different skill set that forced me to crawl under her skin and envision the interplay between a driven woman and, often times, ego driven men—not an easy thing to do.

As I wrote her story, I came to understand what an exceptional woman she really was, and my respect and admiration for her grew and grew. Indeed, I fell in love with her. The book is called, The Postwoman, and the ending, for me, is quite poignant. I’ve read it dozens of times and each time I tear up, and am humbled, recounting the honorable and extraordinary person she was.